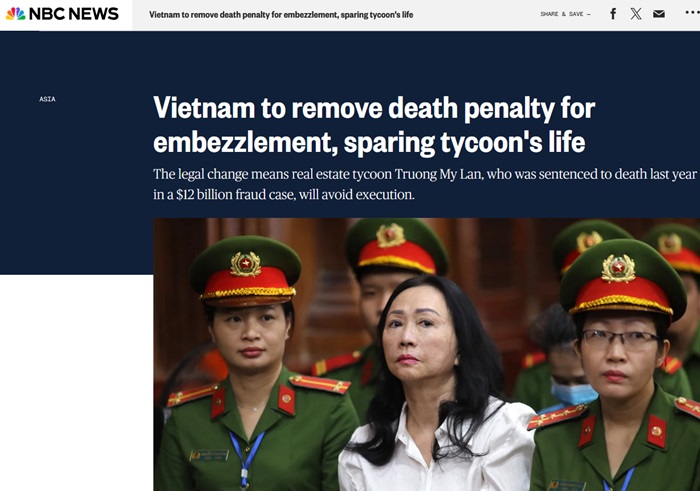

Scammer Truong My Lan

Details |

|

| Name: | Truong My Lan |

| Other Name: | Null |

| Born: | 1956 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | 2024 |

| Age: | 67 |

| Country: | Vietnam |

| Occupation: | Real estate tycoon |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Embezzlement |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | Death In prison |

| Known For: | Null |

Description :

The Woman Who Broke the Bank: Trương Mỹ Lan and the Largest Fraud in Vietnam’s History

Her case has unfolded in several phases: a meteoric rise from a market stall vendor to billionaire magnate, a long period of quiet but expansive influence in real estate and banking, a dramatic collapse involving bank runs and mass prosecutions, and a cascade of trials resulting in multiple life sentences and, for a time, a death sentence. In 2025, major legal reforms abolished capital punishment for embezzlement and similar economic crimes, leading to her death sentence being commuted to life imprisonment. Her story is not only about one individual, but also about the financial system, political patronage, and anti-corruption campaigns in Vietnam, and it echoes similar scandals elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

Early Life and Family Background

Trương Mỹ Lan was born on 13 October 1956 in Saigon, then the capital of South Vietnam. She comes from a Sino-Vietnamese family of Teochew origin with ancestral roots in the village of Gezhou in Shantou, Guangdong, China. Her family, like many other ethnic Chinese families, settled in Chợ Lớn, the historic Chinese quarter of Saigon, in a community known informally as “Little Gezhou.” This neighbourhood had strong commercial traditions and was home to traders, small manufacturers, and shipping families who played an important role in the city’s economy.

Her extended family included entrepreneurs involved in maritime trade. An uncle of hers founded the maritime business Hòa Thuận Phát, which operated in the Chợ Lớn area. Growing up in this environment exposed Lan to a culture of hustle, commerce, and informal networks. While not born into the kind of corporate wealth she would later command, she did grow up in a milieu where business savvy, risk-taking, and close community relationships were essential to success.

Little is documented about her formal education, but her early life was marked more by practical entrepreneurship than by elite schooling. As a young woman, she helped her mother sell cosmetics and other goods in local markets in Ho Chi Minh City. Through this work she learned the basics of trade: understanding customer behaviour, negotiating prices, and navigating the complex social world of urban markets. These humble beginnings became part of the narrative she later used in court, reminding judges and the public that she started from a street-level business rather than inherited wealth.

Early Career and Entry into Business

Lan initially operated small retail ventures, including a business selling hair accessories and cosmetic products. These enterprises were modest in scale but provided her with an entry point into the city’s commercial networks. As Vietnam began its economic reforms under Đổi Mới from the late 1980s onward, opportunities for private enterprise expanded dramatically. Lan was among those who seized the moment, shifting from micro-scale trading into larger, more capital-intensive sectors.

Her life took a decisive turn when she met and later married Eric Chu Nap-kee, a Hong Kong real estate investor. Their marriage in the early 1990s combined her local connections and understanding of the Vietnamese context with his international capital and experience in property development. Both Vietnamese and Hong Kong media later described Chu as a key influence in the transformation of Lan from a market trader into a major property investor.

The Rise of Vạn Thịnh Phát Group

In 1991–1992, Lan and her husband officially established Vạn Thịnh Phát Group, which began as a company focused on real estate investment, hospitality, and related businesses. Over time, it grew into a vast conglomerate involved in luxury residential projects, office towers, hotels, shopping centres, and financial services.

Vạn Thịnh Phát quickly became synonymous with prime land in Ho Chi Minh City. Among its signature projects were the Windsor Plaza Hotel, which hosted events such as the 2006 APEC summit, as well as Times Square, Union Square, Sherwood Residence, and a string of high-end mixed-use developments and planned urban projects like Mũi Đèn Đỏ. These properties were concentrated in central districts and along strategic roads, making the group one of the most important private landowners in the city.

State media and independent observers frequently questioned how Vạn Thịnh Phát managed to secure so many valuable sites in such a short period. Reports suggested that Lan had cultivated close ties with influential political families in Ho Chi Minh City. Some articles pointed to connections with the family of former Politburo member and city party secretary Lê Thanh Hải, although Lan herself was not formally linked to senior office. In 2011 she was awarded the Third Class Labour Medal by the then-president, a decoration that symbolised the state’s recognition of her business contributions, even as doubts about her methods swirled beneath the surface.

By the early 2010s, Lan’s family was considered one of the wealthiest in Vietnam. Her holdings extended beyond Vietnam’s borders, and her name appeared in the Panama Papers in 2016 as a supposed beneficiary of offshore companies used to hold assets. Vạn Thịnh Phát and its related firms were said to number in the hundreds, if not more than a thousand, forming a dense and complex corporate web.

Building Hidden Control Over Saigon Commercial Bank

\If Lan’s property empire made her rich and powerful, her influence over Saigon Commercial Bank (SCB) would later be cited as the core instrument of the fraud. In 2011, Vietnam’s central bank orchestrated the merger of three troubled banks—SCB, Ficombank, and TinNghiaBank—into a new SCB entity. The goal was to stabilise the financial system by rescuing weaker banks through restructuring, with help from private investors.

Lan, already a prominent figure in Ho Chi Minh City’s business scene, became involved in this process. She later claimed that the State Bank of Vietnam invited her to help rescue the merging institutions by committing capital, supporting liquidity, and attracting foreign investment. Officially, she appeared to own only about 5% of SCB’s shares, which is the maximum stake a single individual is legally allowed to hold.

Prosecutors, however, argued that this public picture hid the reality. Through dozens of intermediaries, nominees, and “representative shareholders,” Lan is alleged to have exerted indirect control over more than 85%—and eventually over 91%—of SCB’s shares. In effect, this gave her the power to direct the bank’s lending and investment decisions, appoint key executives, and use SCB as an internal financing arm for her corporate ecosystem.

From roughly 2012 onward, investigators say, she turned SCB into a pipeline of credit for Vạn Thịnh Phát and its network of shell companies. More than ninety percent of the bank’s loans went to entities linked to her group, often backed by inflated or dubious collateral valuations. Many loan applications were later described by prosecutors as fictitious, designed only to move money out of SCB and into projects controlled by Lan, with little realistic prospect of repayment.

Bond Cancellations, Panic, and the SCB Bank Run

The system began to unravel in October 2022. On the surface, the trigger was not a bank failure but a bond issue. Vietnamese regulators cancelled nine bond offerings worth 10,000 billion dong issued by An Đông Group, a key subsidiary of Vạn Thịnh Phát. This raised immediate questions about the group’s financial health and the legitimacy of its fundraising.

Although An Đông was not officially a shareholder of SCB, the public had long perceived the bank and Vạn Thịnh Phát as deeply intertwined. As rumours spread, depositors became frightened that SCB might be dragged down by problems at Lan’s companies. Starting from 6 October 2022, crowds began queuing at SCB branches across Vietnam to withdraw their money. At some locations, customers arrived as early as two in the morning, creating scenes of anxiety and chaos.

The situation worsened on 8 October 2022, when police arrested Lan on charges related to bond fraud and bank mismanagement. News of her detention intensified fears that SCB could be insolvent. The State Bank of Vietnam quickly stepped in, placing SCB under special control and pledging to guarantee its liquidity. Authorities also cracked down on individuals accused of spreading “false information” that might incite further panic.

Even with these interventions, the bank run exposed the fragility of trust in the financial system and highlighted the risk of concentrated, opaque ownership structures. It also set the stage for one of the most sweeping financial investigations in Vietnam’s history.

The Expanding Investigation and Criminal Charges

Following Lan’s arrest, investigators began unraveling a decade’s worth of financial transactions involving SCB, Vạn Thịnh Phát, and hundreds of related companies and individuals. The investigation revealed a vast network of shell corporations, fictitious lending, and questionable bond issuances.

Lan was formally accused of using 916 fake loan applications between February 2018 and October 2022 to appropriate more than 304 trillion dong, or roughly US$12.5 billion, from SCB. She was also charged with illegally issuing bonds in 2018 and 2019, defrauding tens of thousands of investors.

The investigation did not stop with her. More than 80 co-defendants were eventually brought into the case, including senior SCB executives, officials from the State Bank of Vietnam, inspectors from government auditing agencies, and associates within her corporate network. By late 2023, over 100 people had been implicated, demonstrating that her alleged crimes depended on systemic collusion and regulatory failure, not simply individual cunning.

Phase 1 Trial: Embezzlement, Bribery, and Lending Violations

The first-instance trial of Phase 1 opened on 5 March 2024 at the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court. It was an enormous judicial undertaking: ten prosecutors, around 200 defence lawyers, 86 defendants, and 2,700 witnesses took part. The courtroom became a stage not only for legal arguments but also for broader public debates about corruption, power, and accountability.

In this phase, Lan faced three major charges: embezzlement of property, bribery, and violating lending regulations in the operations of credit institutions. Prosecutors argued that from 2012 to 2022, she had effectively “gutted” SCB by orchestrating more than 2,500 sham loans. These loans, they said, led to disbursements of over one million billion dong, accounting for about 93% of SCB’s outstanding debt. As of the prosecution date in October 2022, some 1,284 loans remained active, with total debt, including principal and interest, approaching 677 trillion dong.

During the proceedings, Lan denied many of the accusations while admitting some involvement. She claimed that her primary intent was to save and stabilise SCB rather than enrich herself personally. She also described private interactions with state banking officials and insisted she had been encouraged to participate in the bank merger to prevent a systemic collapse. At the same time, she rejected the accusation that she had ordered bribes to be paid, even when other defendants, such as inspector Đỗ Thị Nhàn, admitted to accepting large sums to produce favourable oversight reports.

Despite her efforts, prosecutors recommended the death penalty, arguing that the scale of her actions, the damage caused to SCB and the wider financial system, and the involvement of bribed regulators made her case extraordinary in its severity.

On 11 April 2024, the court issued its verdict. Lan was found guilty on all major counts and sentenced to death for embezzlement, plus 20 years for bribery and 20 years for lending violations. Since the death sentence is the harshest penalty, it became the operative sentence. Civilly, she was ordered to compensate SCB more than 673.8 trillion dong, reflecting the massive damage attributed to her actions. Her husband received nine years in prison, her niece seventeen, and other defendants sentences ranging from suspended terms to life imprisonment.

Appeals and the Race to Repay

Lan lodged an appeal, arguing that the death penalty was disproportionate and that the loss calculations were flawed. In a hand-written petition, she insisted that she had not personally benefited to the extent alleged and that many of the loans were used to develop projects which retained significant value. She also contested the valuations of collateral assets, such as major real estate projects that she said were priced at far below their actual market worth.

During the appellate hearings in late 2024, she and her lawyers stressed that her family had already begun paying back hundreds of billions of dong and that she was actively seeking to sell properties and collect debts owed to her. They argued that she needed time and legal stability—preferably under a life sentence rather than a death sentence—to negotiate sales, restructure assets, and maximise recovery for the state and SCB.

On 3 December 2024, the High People’s Court upheld her death sentence but added an important conditional pathway: if she could repay three quarters of the embezzled amount, roughly US$9–11 billion, her sentence could be commuted to life imprisonment. This formalised what had already been hinted at in earlier proceedings—that large-scale restitution could serve as a basis for clemency.

This decision effectively placed her in a race against time. While the law did not require immediate execution, Vietnam’s use of capital punishment is opaque, and prisoners typically receive little notice before an execution is carried out. From that moment, Lan’s life depended not only on legal appeals but also on her ability to mobilise vast sums, liquidate frozen assets, and convince the authorities that substantial restitution was realistic.

Phase 2: Bond Fraud, Money Laundering, and Cross-Border Transfers

While Phase 1 focused on SCB loans and embezzlement, Phase 2 of the case dealt with bond fraud, money laundering, and illegal cross-border money transfers. Investigators alleged that between 2018 and 2020, Lan directed a set of Vạn Thịnh Phát subsidiaries to issue 25 fictitious bond codes. These bonds, totalling massive sums, were used not to raise legitimate capital but to disguise and recycle funds within her corporate network.

Prosecutors argued that this scheme defrauded over 35,824 bond investors, many of whom believed they were purchasing safe, high-yield financial instruments backed by reputable firms. In reality, the proceeds were supposedly used to repurchase the bonds through other related companies, creating a closed loop that masked the true origins and destinations of the money.

In addition, authorities accused Lan and her associates of orchestrating more than 78 illegal cross-border transactions through over 20 companies. These transactions, worth about US$4.5 billion, allegedly involved transferring money out of Vietnam and bringing funds back in through illicit channels, thereby laundering proceeds and bypassing official controls. The sums involved were equivalent to roughly 1% of Vietnam’s 2022 GDP, underlining the scale of the operations.

The second first-instance trial, which began on 19 September 2024, brought 34 defendants before the court. Lan once again denied using SCB’s funds solely for personal benefit, arguing that some transfers were part of legitimate investment and restructuring efforts. Yet she also expressed deep remorse in her final statements, apologising to thousands of victims and acknowledging that her decisions had inflicted widespread harm.

On 17 October 2024, the court sentenced her to life imprisonment for embezzlement, 12 years for money laundering, and eight years for illegal cross-border money transfers, with the combined sentence set as life imprisonment. She was ordered to compensate bond investors more than 30,081 billion dong, adding a new layer of civil liability on top of the SCB losses from Phase 1.

Appellate Decisions in Phase 2 and Sentence Adjustments

Lan appealed the Phase 2 verdict as well. The appeal hearings, held in early 2025, examined her claims about asset valuations, restitution efforts, and her willingness to collaborate in restructuring SCB and compensating victims. By March 2025, the civil enforcement authorities had already received tens of thousands of information requests from bondholders seeking compensation, reflecting the sheer number of people affected by the schemes.

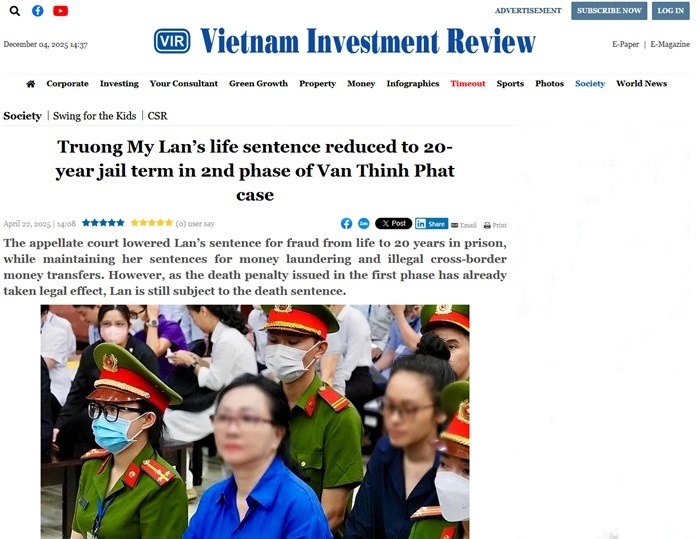

On 21 April 2025, the appellate court reduced her sentence for “fraudulent appropriation of assets” from life imprisonment to 20 years, citing her partial cooperation and the progress in recovering assets. Her sentences for money laundering and illegal cross-border transfers were upheld. However, because the death penalty from Phase 1 remained in legal force, these adjustments did not immediately change her overall status: she was still, technically, under a death sentence for embezzlement.

Legal Reforms and Commutation of the Death Penalty

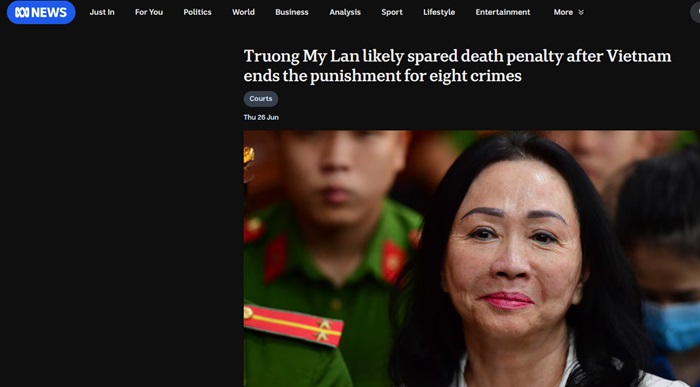

The decisive shift came in June 2025, when Vietnam passed major legal reforms that abolished the death penalty for several economic and political crimes, including embezzlement, corruption, certain drug and state-related offences. The law retained capital punishment only for the gravest crimes, such as murder, terrorism, treason, child rape, and some forms of drug trafficking.

Crucially, the new legislation stipulated that individuals who had already received death sentences for the abolished offences but had not yet been executed by 1 July 2025 would have their sentences commuted to life imprisonment after a final review by the highest court. As Lan’s death sentence was based on embezzlement and related financial crimes, she became eligible for commutation.

Her lawyers confirmed that under the new legal framework her death sentence would be converted to life in prison, likely without the possibility of parole. They also noted that continued restitution could still play a role in future sentence reductions or improvements in her detention conditions, although she would remain incarcerated for the rest of her life.

This legal change effectively removed the immediate threat of execution and turned her case into a long-term saga of asset recovery, civil compensation, and ongoing scrutiny of the financial and political systems that allowed her rise in the first place.

Personal Wealth, Assets, and Attempts at Restitution

Throughout the trials, one of the most striking elements was the sheer scale of Lan’s wealth and how it intersected with her legal predicament. At various points, she claimed that selling only a small fraction of her real estate holdings could generate enormous sums, and that her overall asset value might exceed the compensation required by the courts.

In May 2025, while in prison, she wrote to authorities requesting a new valuation of her assets, arguing that the previously assessed figure of 253.5 trillion dong undervalued her holdings. She asked to take part in the valuation process herself, claiming her goal was to maximise returns for the state, SCB, and investors. Her lawyers also argued that condemning her to death made it harder to secure favourable prices for asset sales, as buyers would see her situation as unstable and urgent, encouraging lowball offers.

By early April 2025, prosecutors reported that about 8 trillion dong had already been collected from her assets, with an additional 15 trillion expected from other individuals and entities. In total, more than a thousand separate assets had been identified and frozen, including luxury buildings, development projects, shares in companies, and other forms of property. The complexity of this portfolio made liquidation time-consuming and legally complicated.

Despite the commutation of her death sentence, the financial dimension of the case remains unresolved and will likely continue for years, as courts, banks, and enforcement agencies attempt to convert frozen assets into compensation for SCB and tens of thousands of victims.

Key Associates and Co-Defendants

Lan did not act alone. Her husband, Eric Chu, was tried in both phases and ended up with a total of about eight years in prison for his role, particularly in helping create false documents that enabled SCB to grant loans favourable to Vạn Thịnh Phát companies.

Her niece, Trương Huệ Vân, served as general director of Vạn Thịnh Phát and managed many of its subsidiaries. She admitted to establishing dozens of shell companies and signing fictitious contracts that supported fraudulent loans and bond issuances. She received lengthy prison terms in both phases, though some were reduced on appeal.

On the regulatory side, Đỗ Thị Nhàn, a senior official in the State Bank’s inspection and supervision department, was found guilty of accepting a US$5.2 million bribe from Lan’s representatives in exchange for favourable inspections. Despite returning the illicit funds, she was sentenced to life imprisonment, as the court deemed her conduct gravely damaging to the financial system’s integrity.

Former SCB CEO Võ Tấn Hoàng Văn and former chairman Bùi Anh Dũng were likewise sentenced to life in prison for their central roles in issuing hundreds of fraudulent loans, signing off on documentation, and facilitating Lan’s use of the bank as a private funding arm. Their convictions underscore that the scandal was not a one-woman operation but a systemic failure involving multiple layers of management and regulation.

Wider Anti-Corruption Context in Vietnam

Lan’s downfall occurred against the backdrop of Vietnam’s intensified anti-corruption drive, widely referred to as the “blazing furnace” campaign led by Communist Party General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng. This campaign has targeted officials, business leaders, and state-owned enterprise executives, aiming to restore public trust and reassure investors that corruption will not be tolerated.

Her case became the flagship example of this effort. The size of the losses—equivalent to around 3% of Vietnam’s 2022 GDP in just one portion of the fraud—raised alarm about the strength of banking supervision, the independence of regulatory bodies, and the potential for politically connected tycoons to manipulate the system. Authorities emphasised that the harsh sentences and sweeping investigations were intended not only to punish, but also to deter future abuses and to show that even the most powerful are not above the law.

At the same time, the scale of the scandal exposed serious systemic problems. It highlighted how opaque ownership structures, weak oversight, and cosy relationships between regulators and regulated institutions can create fertile ground for massive frauds. This tension—between the need to punish wrongdoing and the need to acknowledge institutional failings—continues to shape public debate in Vietnam.

Parallel Corruption Scandal: Elizaldy “Zaldy” Co in the Philippines

Lan’s case is not unique in Southeast Asia. In the Philippines, former congressman Elizaldy “Zaldy” Co, once chair of the powerful House appropriations committee, is accused of engineering a vast “ghost flood-control” scheme. This involved allocating billions of pesos to flood-control projects that were substandard, overpriced, or entirely fictitious, with funds allegedly funnelled to contractors who returned large kickbacks.

One especially controversial discovery was Co’s private fleet of aircraft: at least 13 planes and helicopters registered to companies linked to him, including a Gulfstream G350 executive jet and multiple AgustaWestland helicopters. The size of the fleet outstripped that of the Philippine Coast Guard, provoking public outrage and symbolising the stark disparity between public needs and private luxury.

As investigations intensified, some aircraft tied to Co were flown to Singapore and Malaysia, seemingly in an attempt to move them out of reach of Philippine authorities. However, the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines, working with anti-money laundering agencies, blocked the deregistration of these aircraft. Under international aviation law, planes cannot be re-registered abroad without formal deregistration in their home country, which effectively froze their legal transfer and resale value.

Co resigned from Congress citing “grave threats” to his safety and denied the accusations, while leaving the country on the pretext of medical treatment. His current whereabouts remain unclear, and authorities have requested Interpol assistance. The scandal has fed public anger over systemic corruption and triggered renewed calls for transparency in the Philippine budget process.

Political Accountability in Malaysia: The Support Letter Controversy

In Malaysia, a smaller but symbolically significant episode of political controversy unfolded when Shamsul Iskandar Mohd Akin, a senior political secretary to the prime minister, resigned following revelations that he had issued a letter of support for certain contractors bidding on a hospital project. The letter, which named specific companies and was seen as an attempt to influence procurement, sparked criticism from opposition politicians and the public.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim confirmed in parliament that he had reprimanded a political secretary for issuing such a letter and reiterated that the government’s policy was to avoid any form of endorsement in public tenders. At most, he said, an official could write “please review” when forwarding documents, but could not recommend specific companies.

Shamsul stated that he stepped down to avoid damaging the government’s image and to defend himself outside the constraints of office. While the sums involved were nowhere near the astronomical figures in the Vietnamese and Philippine cases, the controversy underscored growing sensitivity to conflicts of interest and the use of political influence in public contracting. It also showed that even relatively small acts of perceived favoritism can carry significant political cost in a region increasingly aware of corruption’s broader social impact.

The rise and fall of Trương Mỹ Lan encapsulate some of the most pressing issues confronting rapidly developing economies: how to balance growth with oversight, how to encourage private enterprise while preventing financial capture, and how to hold the powerful to account without undermining investor confidence. From her beginnings as a market vendor to her role as chairwoman of one of Vietnam’s largest private conglomerates, she became a symbol of extraordinary wealth and influence. But her alleged transformation of a major bank into a private source of funds, her involvement in opaque bond schemes, and the colossal losses inflicted on SCB and tens of thousands of investors turned her into the face of unprecedented financial crime.

Her death sentence in 2024, later commuted to life imprisonment under 2025 legal reforms, represents both the severity with which Vietnam now treats large-scale corruption and the evolving nature of its penal policy. At the same time, parallel scandals in the Philippines and controversies in Malaysia show that Vietnam is not alone in confronting such challenges. Across Southeast Asia, citizens are demanding cleaner governance, stricter oversight, and genuine accountability for those who abuse public trust and financial systems.

Lan’s story is far from over. The courts and enforcement agencies will continue to chase restitution, liquidate her sprawling portfolio, and compensate victims. But whatever the final financial tally, her case will remain a reference point—a warning about how much damage can be done when institutional safeguards are weak, regulatory capture is tolerated, and immense power is concentrated in private hands with too little scrutiny.